Neil Rowe, senior in-house counsel at THEMIS Clinical Defence, examines the current proposals and suggested improvements for costs in medical negligence claims.

Costs incurred in clinical negligence claims are significant and most (if not all) practitioners would agree that the costs incurred in low-value claims for damages are disproportionate. A small proportion of cases reach litigation, but for the vast majority of cases, there is no real control over costs in the pre-action stage or litigation phases up to that point.

Reform is therefore needed.

The proposal to apply fixed recoverable costs (FRC) to low-value clinical disputes (LVCD), was intended to create a greater degree of predictability and proportionality, by reducing overall litigation costs, encouraging efficient working, creating a transparent costs structure, and promoting access to justice for some who may otherwise be unable to litigate.

Strangely a two-pronged approach developed rather than a single one.

The Ministry of Justice (MOJ) has introduced a new, intermediate track comprising cases valued between £25,000 and £100,000, which applies to clinical negligence claims where liability has been admitted and only the amount of damages is to be determined. These changes were accepted by the MOJ back in September 2021 and subsequently implemented from the beginning of October 2023.

On the other hand, it has been three years since the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) first consulted on FRC for claims worth up to £25,000. Their proposed LVCD Protocol was expected to be launched in April and then (following the change of government) in October last year but at the time of writing there is no hint of when it may be implemented.

Have I got news for you

The LVCD Protocol plans to operate as follows:

- All clinical negligence claims with a value at settlement or following judgment between £1,501 and £25,000 (even if it was valued over £25,000 at the outset and didn’t follow the LVCD Protocol) will be subject to fixed costs unless they qualify for a specified exclusion.

- If a specified exclusion applies, the claim will not be limited to the fixed costs and the claim falls within the standard pre-action protocol.

- Specified exclusions include where the claimant is a litigant in person; the claim involves a stillbirth or neonatal death; there are to be more than three medical experts addressing breach of duty and causation; the defendant raises limitation as an issue; or there are two or more defendants.

- A dual process will be implemented with two separate tracks, the standard track and the light track. Cases should progress on the standard track unless they meet certain conditions for the light track. It will be for claimants to determine which track is most appropriate for the claim.

- Light track cases are for situations where the parties do not anticipate a dispute over liability.

- Compared to the current pre-action protocol the process is frontloaded so that the letter of claim served by the claimant is now accompanied by an indexed sorted paginated bundle of the claimant’s medical records, expert report(s), up to two witness statements and crucially an offer to settle the claim.

- Both track process provides for mandatory stock take and discussion. Failure to participate will lead to costs.

- Ultimately whether a claim will continue on the light track will be determined by whether the defendant admits breach of duty of care. If not, it reverts to the standard track.

The price is right?

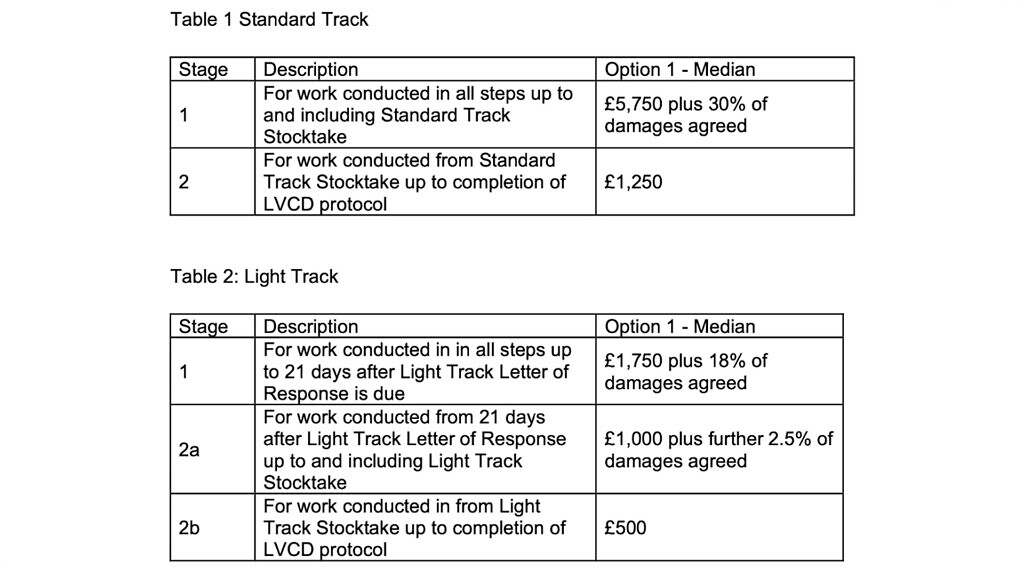

For these low-value clinical disputes, fixed recoverable costs apply to pre-action cases. If the claim settles within the protocol the amount recoverable depends on the track and stage reached.

The following has been proposed:

Deal or no deal?

There are clearly some contentious areas in the proposals. The main issues are the level of damages to which it applies, the fixed fee amounts, the claimant’s choice of track, exceptions, plus the number of experts and their fees.

Most defendants would no doubt argue that the damages limit should be increased to say £50,000 so that many more claims would be subject to FRC. Many claimants argue the introduction of FRC will mean that securing a specialist clinical negligence lawyer will be difficult as some will struggle to make a profit with the fees proposed and so turn cases away. Moreover, increasing the limit by a further £25,000 would make matters even more difficult.

The fixed fees are challenged by many claimants as too low – a maximum of up to £14,500.

That said they have been carefully formulated by the DHSC and the figures are certainly proportionate. A sensible compromise approach would be to keep the limit to £25,000 and the fixed fees as proposed so DHSC can review the number of cases going through the scheme and better assess the access to justice argument.

There is scope for disagreement on the exceptions and conditions which will determine how many cases will fall within the scheme and on which track.

Equally, claimants may try to argue that conditions do not apply so that the more lucrative standard track is appropriate rather than the light track. Rather than encourage satellite disputes over definitions of never events, the contents of investigation reports, or whether the facts speak for themselves, it would probably be more certain to rely on clear admissions of liability.

Clinical negligence claims are driven by expert evidence and often the bulk of costs claimed are made up of expert fees which are higher than the lawyers’ fees. It is therefore surprising that there is no proposal to limit expert fees in the same way as those of the lawyers. Considering the figures set out above, it should be possible for experts to produce suitable reports within capped or fixed fees between say £1,000 and £2,500 so that disbursements overall remain proportionate.

They think it’s all over

While many clinical negligence lawyers might have reservations about the current fixed recoverable costs proposals the need for reform remains. Rather than continuing to be overlooked, it is hoped that the scheme is piloted soon and then changes made where necessary to achieve balance between the parties and in the interests of costs proportionality and justice.