Richard Duggins, consultant psychiatrist and psychotherapist in the NHS, believes that with the right awareness and action, burnout can become the exception, not the norm.

A man and a woman are sitting beside a fast-flowing river. Suddenly, they see someone drowning in the water. They dive in to rescue them. Five minutes later, another person floats by, and they dive in again. This continues until the woman asks, “Do you think we should walk upstream and find out why they’re all falling in?”

This story, often attributed to Bishop Desmond Tutu, captures the shift I’ve made over the past 20 years as a doctor. I began my career in a mental health clinic treating professionals with burnout. Most of the people I initially treated were doctors, which soon led to my nickname: the doctors’ doctor. Over time, I became more curious about what was happening upstream. Why were so many bright, caring professionals burning out in the first place?

The term burnout was first coined by Herbert Freudenberger, a psychoanalyst in 1960s New York. He experienced it himself. Long days treating people in a public clinic, followed by evenings with private clients, left him emotionally depleted and physically unable to continue. He described it as a “smouldering” exhaustion of the spirit. Like a fire-damaged burnt-out building, outwardly intact but inwardly destroyed.

A few years later, US social psychologist Christina Maslach, professor emerita of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, identified three core features of burnout: overwhelming exhaustion, emotional detachment and a loss of joy in work.

Burnout is treatable

Burnout is no longer a fringe issue. Rates spiked during the pandemic and remain stubbornly high. Healthcare, especially medicine, is the highest-risk profession for burnout in the UK. The GMC has raised concerns about a vicious cycle with burnt-out doctors needing leave which increases pressure on those who remain, who then also burn out.

The consequences are serious, not just for individuals and families, but for organisations too. Burnout drives sickness absence, turnover, low morale, errors and reduced productivity. In healthcare, it’s linked to poor communication, weaker teamwork, complaints, and patient safety risks. And yet, burnout is treatable and crucially, preventable.

One of the most important things I’ve learned is that burnout isn’t caused by who we are, but by what happens to us. It’s not a personal weakness. In fact, it often affects the most dedicated people. Those who push on too long without the right support.

To explain burnout, I often use the metaphor of drains and radiators. Drains sap energy, and are things like work stress, home pressures and negative feelings about work. Radiators restore it, through good support, fun and social time, and stimulating or developmental opportunities. Burnout happens when the drains outweigh the radiators for too long.

That balance is shaped far more by workplace culture and leadership than by personal resilience.

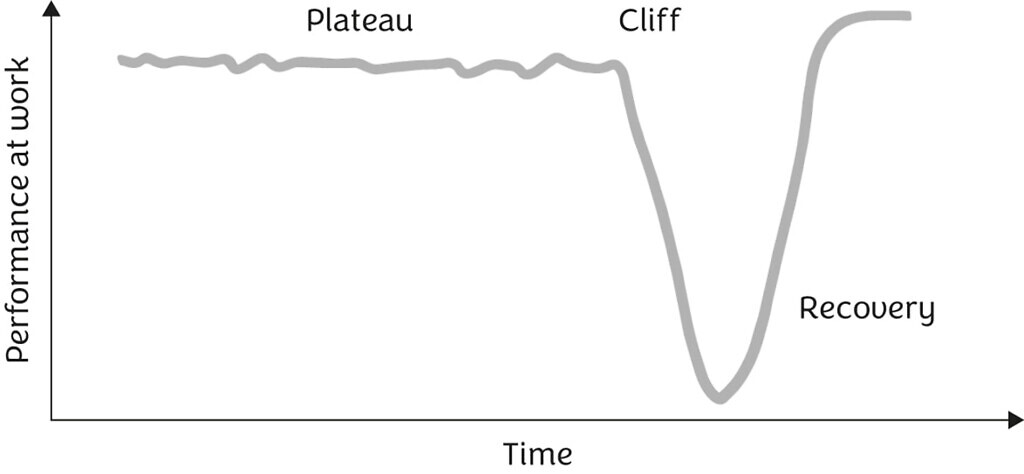

I first noticed the Burnout Cliff through the stories of hundreds of doctors I was treating. Their circumstances varied, but a common pattern emerged. I captured it in a simple sketch I called the Burnout Cliff.

The Burnout Cliff shows a typical performance pattern: a long decline (the Plateau), a catastrophic collapse (the Cliff), and, given the right support, a hopeful Recovery.

The Plateau is where doctors feel increasingly exhausted and stressed. Pressures at work and home build. They keep going, still appearing high performing but are increasingly internally depleted. This phase often lasts six months to two years.

Then comes the Cliff. One doctor told me, “I didn’t realise I was burning out until it was too late. I thought it was just a long, busy spell”. The collapse is often sudden.

One consultant had felt exhausted and joyless for months, but when his son’s teacher contacted him about a problem at school, his resilience finally crumbled. He had to phone in sick, for the first time in his career.

Recovery can be surprisingly swift with the right support. But it’s not just about rest. It’s about reducing the drains and restoring the radiators.

Recovery is possible

Why do so many committed people journey along the Plateau until they fall? In survival mode, we stop doing the things that help us cope and focus solely on work. We fear appearing weak or letting others down. Shame and stigma, especially in medical culture, make it hard to ask for help. Our world narrows. Energy drains. Then something gives.

And yet, recovery is possible, and it can be transformative.

Strong recoveries have layers. Like firefighters’ gear, one layer alone isn’t enough. First, people address basic unmet needs, like workload, breaks, and support. Then they decompress. They run, walk, cook, sing. Matt Morgan, an ICU consultant, calls this “squeezing the sponge”. He sees himself soaking up stress during the day, and decompressing is how he wrings it out.

Next, people reconnect with others. They replace unhelpful coping habits, like overworking, drinking or withdrawing, with healthier ones. And they learn to spot the early warning signs of problem stress. They shift from “Keep calm and carry on” to “Keep calm and nip it in the bud”.

Of course, it’s our organisations that can make the biggest difference. They must look upstream at the systems and cultures that push doctors toward the cliff. This means more than token well-being washing gestures like mindfulness sessions no one has time to attend. Leaders, especially medical leaders, need to be psychologically savvy, proactively reaching in, and not just waiting for people to reach out. It’s easier for doctors to speak up if the culture routinely checks in and shows genuine care.

The workplace must also evolve, with fair processes, flexibility, workforce planning, good facilities, and time for reflection and peer support.

One of the great privileges of my work is witnessing recovery and growth. I’ve seen people emerge from burnout wiser, stronger, and more connected to their values.

Recovery is possible but prevention is better. Burnout is not a rite of passage or the price of doing important work. With the right awareness and action, burnout can become the exception, not the norm. And when we look upstream, we don’t just rescue people. We create workplaces where they never fall.

Richard Duggins is a consultant psychiatrist and psychotherapist in the NHS. He leads the North East and North Cumbria Staff Health and Wellbeing Hub and works with NHS Practitioner Health. He is the author of Burnout-Free Working. Get 25% off the book with the code HEALTHCARE25, exclusively on the JKP website.